Bedknobs and Broomsticks: A Modern Golem Tale?

Today I rewatched Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), which I viewed probably hundreds of times before age seven but never since, as we didn’t own the VHS. I can’t say that I’d recommend it to anyone now even though it’s technically a “classic” - it’s agonizingly long and the Portobello Road song sequence, while perhaps trying to do some sort of “It’s A Small World” schtick, comes off as deeply cringe. Also, this may be a small bone to pick, but the characters, who are living in WWII England during the Blitz, refer to football as “soccer”; a glaring faux pax. But the opening credits contained the below image, reminiscent of the Rider Waite Hermit, performing a gesture evocative of the sign of silence, and wearing a cloak of astrological symbols, so I kept on for two hours to see what else cropped up.

The source material for Bedknobs and Broomsticks is based upon two books written by Mary Norton in the 1940s (who also, incidentally, wrote The Borrowers). However, I’m uncertain how heavily her work was adapted for the screen.

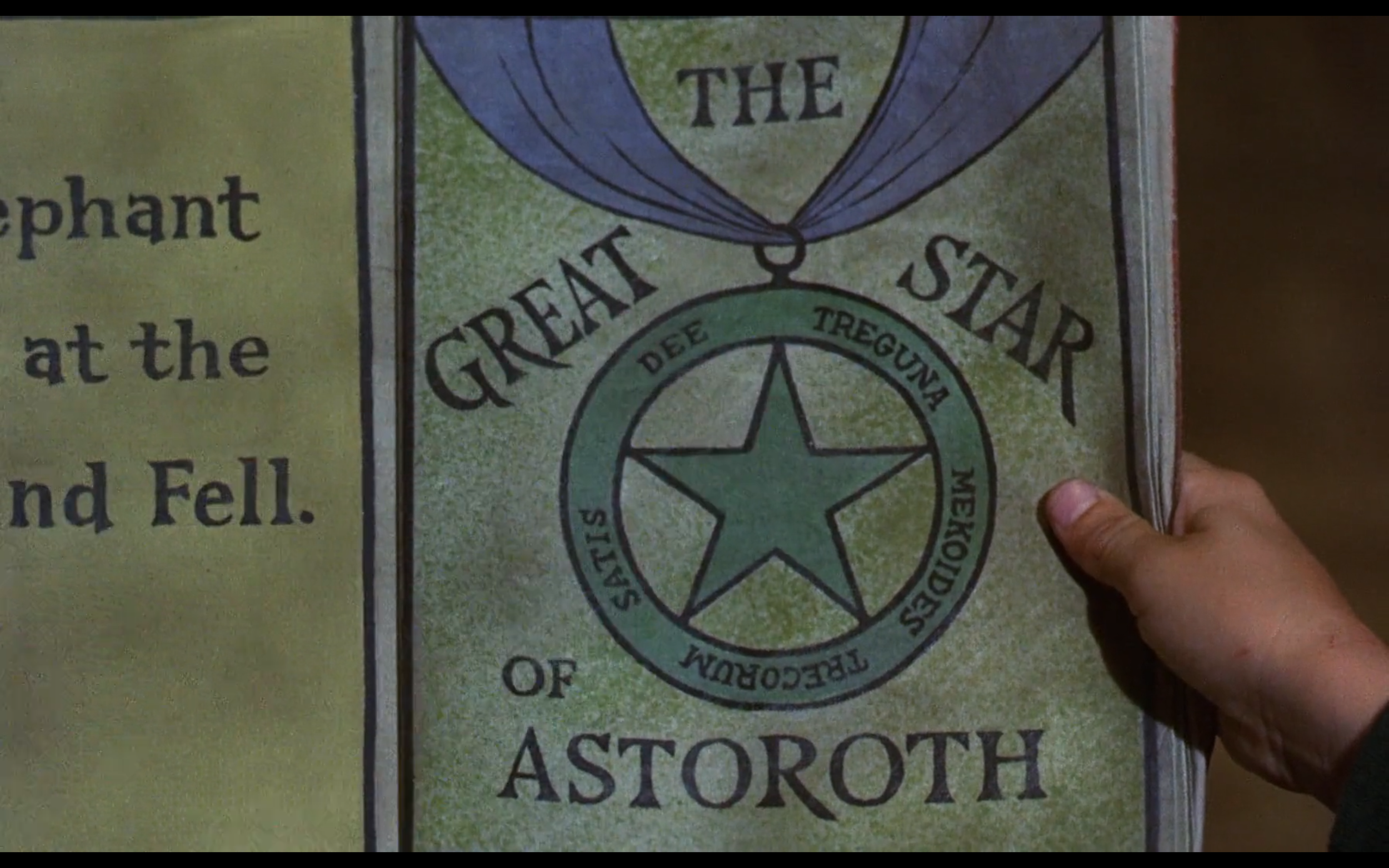

What becomes clear a painful 40 minutes into the film is that the writers had some familiarity with the antics of Aleister Crowley. The plot revolves around the Bedknobs crew trying to obtain a magical amulet called The Star of Astoroth, a word that would make any esoteric student’s ears perk up.

The name Astaroth (with slight spelling alteration) first appears in print in The Book of Abramelin, dated to either the 14th or the 17th century, and initially composed in either Hebrew or German, depending on which scholar you ask. In the book, Abraham of Worms recounts his travels to Egypt to learn from the titular Abramelin, a Kabbalistic mage. It details a ritual working intended to contact one’s Holy Guardian Angel, and in this composition, Astaroth is a demonic title. Astaroth would be mentioned in several subsequent grimoires, including The Lesser Key of Solomon, so it was strange to hear it referenced, without further explanation, in the context of a whimsical children’s film.

Translated into English by S.L. MacGregor Mathers in 1897, The Book of Abramelin would be influential in his Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which thus inspired Crowley to attempt the Abramelin ritual at the infamous Boleskine House in the first decade of the 1900s. He was interrupted due to schisms in the Golden Dawn which called him back to Paris, which might be a good thing, because Mather’s translation only contained three of Abramelin’s four books.

Why this specific name would show up in a Disney film is unclear, however there is a possible route through Der Golem: wie er in die Welt kam, Paul Wegener’s excellent 1920 silent horror film. In Der Golem, set in medieval Prague, a fictionalized version of Rabbi Loew summons the demon Astaroth to reveal the secret word that will grant him the power to awaken the Golem, an inanimate being made of clay.

Whether there is an explicit connection between Loew and the use of the term Astaroth is unclear, though in all likelihood it is a creative flourish. Wegener’s film is itself an adaptation of the 1914 serialization Der Golem by Gustav Meyrink, who based his tale on Jewish folklore. (Meyrink was NOT of Jewish descent, but studied Kabbalah, theosophy, and the occult, broadly, before converting to Buddism in the 20’s, and could have potentially picked up “Astaroth” through his esoteric interests.)

What IS clear is that Wegener himself later starred in the 1926 film The Magician, where he plays a character based on unflattering (and extra spooky-ookey) depictions of Crowley. Undoubtedly, Wegener would have been familiar with magical jargon on the whole and the antics of certain magical figures of the late 19th/early 20th century in particular.

Now THE WHOLE REASON why the Star of Astaroth is mentioned in Bedknobs and Broomsticks is because Angela Landsbury’s character, Miss Price, wants a spell for something she keeps calling Substitutionary Locomotion, which she intends to use to help the war effort, which is very noble of her. The Star has a magical incantation written on it for this purpose (“Treguna Mekoides Trecorum Satis Dee” which is about as meaningful as “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious”, except I can’t help but think that “Dee” was thrown in there for good measure as a nod to famous astrologer and occultist John Dee). What is eventually revealed, ANOTHER 30 MINUTES LATER, is that this Substitutionary Locomotion spell causes inanimate objects to take on a life of their own. Kind of like…a Golem.

There’s singing and hijinks and finally (FINALLY) Miss Price uses the incantation to bring medieval suits of armor to life and scare off the Nazis, as one does.

So, is Bedknobs and Broomsticks a modern, post-war Golem tale? While the jump from German Expressionist cinema to Disney musical seems odd, Der Golem featured special effects that may have been studied and later emulated by Disney imagineers. And Disney animation had no shortage of wizards, from Fantasia’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice (which is based on a poem by Goethe and also has Golem-esque undertones) to The Sword in The Stone’s Merlin. Magic has been a mainstay of the Disney brand far preceding the Magic Kingdom theme park, which coincidentally opened the same year that Bedknobs was released. If anything, the chief divergence is that the Golem is a cautionary tale about the misuse of magical power, whereas Bedknobs seems to suggest that magic used against an enemy has no ethical consequences. (Miss Price also renounces witchcraft at the end of the film? So, neat.)

Bedknobs and Broomsticks may not be worth your time if you're not under seven or an Angela Landsbury stan, or unless the film holds more nostalgic value for you than it does for me. But it’s reasonable to conceive of a direct line of transmission from the Golden Dawn to Crowley to Der Golem to which Bedknobs and Broomsticks seems to be, at the very least, a conceptual successor.